By Michael Hutchins / Herald Democrat

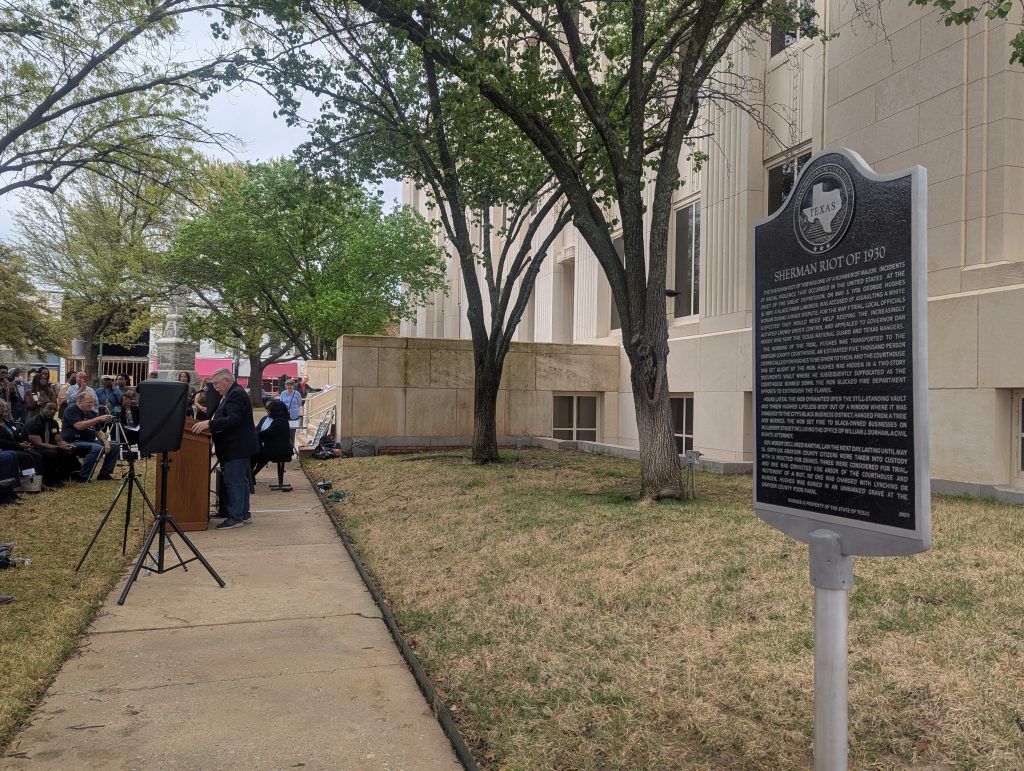

Community leaders gathered outside Grayson County Courthouse Saturday morning to remember a day where racial violence won over the rule of law. Community members and the Texas Historical Commission held an unveiling ceremony for a new historic marker in recognition of the Sherman Riot of 1930.

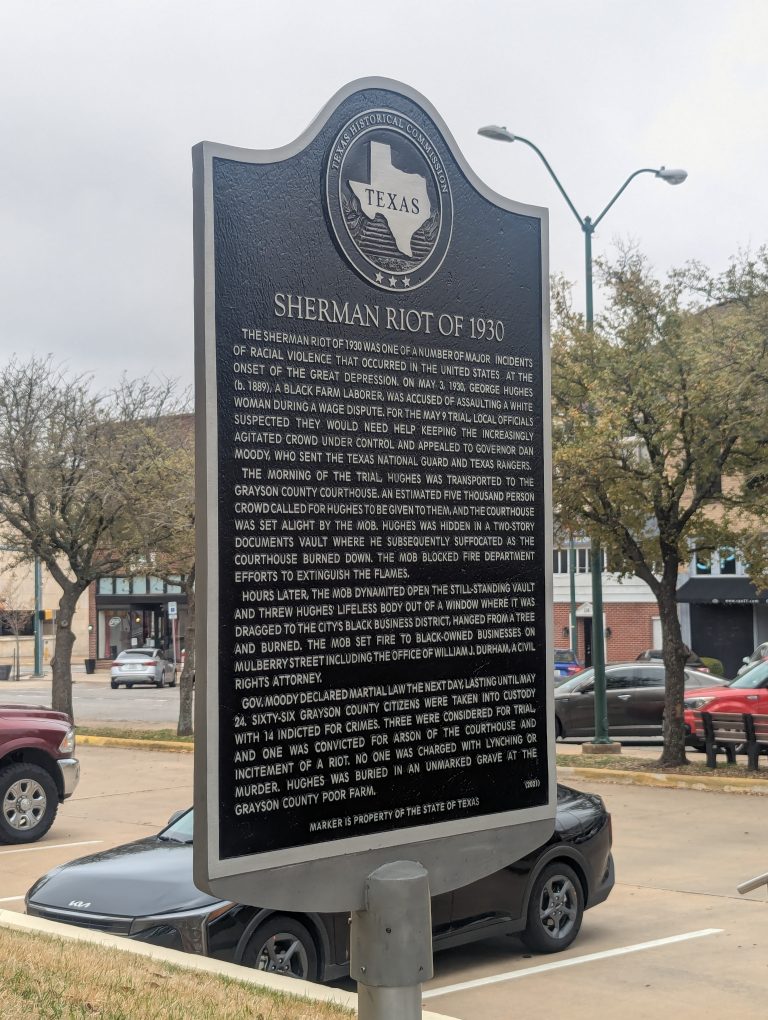

The riot revolved around the trial of Black farmhand George Hughes, who was accused of sexually assaulting the wife of his employer amid a dispute over wages. The situation escalated over the course of a day and ended with Hughes lynched, the Grayson County Courthouse destroyed and Sherman’s Black business district burned to the ground.

“Despite how uncomfortable it is, this event affected real places, real people and real families,” historian Melissa Cole said. “The consequences were real and last to this day. You have to be uncomfortable to grow.”

The new marker sits to the right of the steps of the Grayson County Courthouse, juxtaposed across from a Confederate monument to the left of the steps. While another historic marker on the other side of the courthouse mentions the destruction of the original courthouse, it does not go into detail about the riot itself.

“I would say we are not here to say George Hughes was innocent or guilty,” Cole said. “We are here to say he didn’t get his day in court in our justice system.

“It is supposed to protect everyone, but in the Jim Crow era of 1930 it was not liberty and justice for all; it was liberty and justice for a few. We can see that through the lynchings, not just here in Sherman, but in the state and the nation.”

While some accounts state Hughes was in the process of pleading guilty, Cole said this must be taken within the context of the Jim Crow era. Even if he had pleaded not guilty, it wasn’t certain that he would get a fair trial or that someone wouldn’t attempt to take justice into their own hands.

“They (other trials) usually ended the same way with mobs, lynchings and fake trials where you are going to be found guilty no matter what,” Cole said. “A lot of these people pleaded guilty to stay out of the hands of the mobs. So, you have to look at the court systems, the police and everything that was going on in the justice system and how it did not work out for Black people in the 1930s.”

Tensions continued to grow throughout the day until an office in the courthouse was doused in gasoline and set on fire. Attempts by first responders to put out the blaze were stopped by the crowd, and the fire eventually consumed the building.

Once the fire subsided, the crowd used explosives to gain access to the vault and removed Hughes’ corpse from the building. The body was then dragged behind a car toward Mulberry Street and the city’s Black business district where it was hung from a tree and a bonfire was set underneath. Throughout the course of the night, many of the city’s Black-owned businesses were destroyed and many never recovered.

“I know how important it is to remember history, and one of the really big focuses besides George Hughes — definitely focus on the lynching victim — but there was an entire Black business district that nobody talks about,” Cole said. “You go over to Mulberry Street and you wouldn’t know it was ever there. There is nothing over there talking about it.

“That affected generations of people, and I would have Black citizens come up to me and talk about the Black business district and their parents and grandparents who left.”

Cole’s efforts to have the event memorialized on a historic marker began during another moment of racial violence in America. The idea came to her as she was attending a protest at the Grayson County Courthouse following the murder of George Floyd in Minnesota by a white police officer.

“I thought, you know, in 1930 there was another crowd here, a crowd lynching a Black man, and I have known about it as a historian,” Cole said. “I thought this is something that I can do locally to recognize history and educate people on racism and how that has evolved in the United States.”

Throughout 2021, Cole and other organizers pushed to get consideration on the agenda for the Grayson County Commissioners Court. As the proposed marker site sat on county property, officials would need to grant permission for the marker.

Efforts included a petition with the signatures of more than 700 Grayson County residents and regular speakers during the public comment portion of meetings. In late 2021, the Commissioners Court appointed a committee to advise on the marker request and approved it in October 2021.

In hindsight, Cole attributed the move in part to the recent announcement that Texas Instruments planned to build a new $30 billion production site in Sherman. Cole speculated that this could have put pressure on the community to address the concerns.

“Texas Instruments was coming to town and building their new facility in Sherman and there was the idea that, hey, this looks really bad on us to have this fight over this marker and have it be so public,” she said. “I think Texas Instruments coming played a big role in wanting this not to be such a public debate.”

In 2022, the marker request was accepted by the state commission under its Undertold History program, which seeks to fill gaps in history for groups and topics that are traditionally underrepresented. Since then, the commission has been working with local groups regarding the wording on the marker. Cole said there was some disagreement over if words, including Black, white and lynching, would be used.

Despite the success in getting the marker placed, Cole said the biggest victory is simply bringing attention to the topic. Since the marker effort began, other programs and initiatives aimed at bringing attention to Sherman’s Black history have begun.

“We’ve had a black business district walking tours, there are murals on the side of the Sherman Library, Grace United Methodist Church does the George Hughes memorial scholarship,” she said. “… All of the education, recognition and everything that has gone on between the start and end of the marker process probably means just as much as the marker to educating the community.”

Still, Cole said she expects the marker unveiling will be an emotional moment for many, including herself.

“To actually have started the process, taking five years, and have it done, it feels amazing,” she said. “I think what feels even better is all the work from the community.”